If you're a game developer, 2019 is the year you adapt or die.

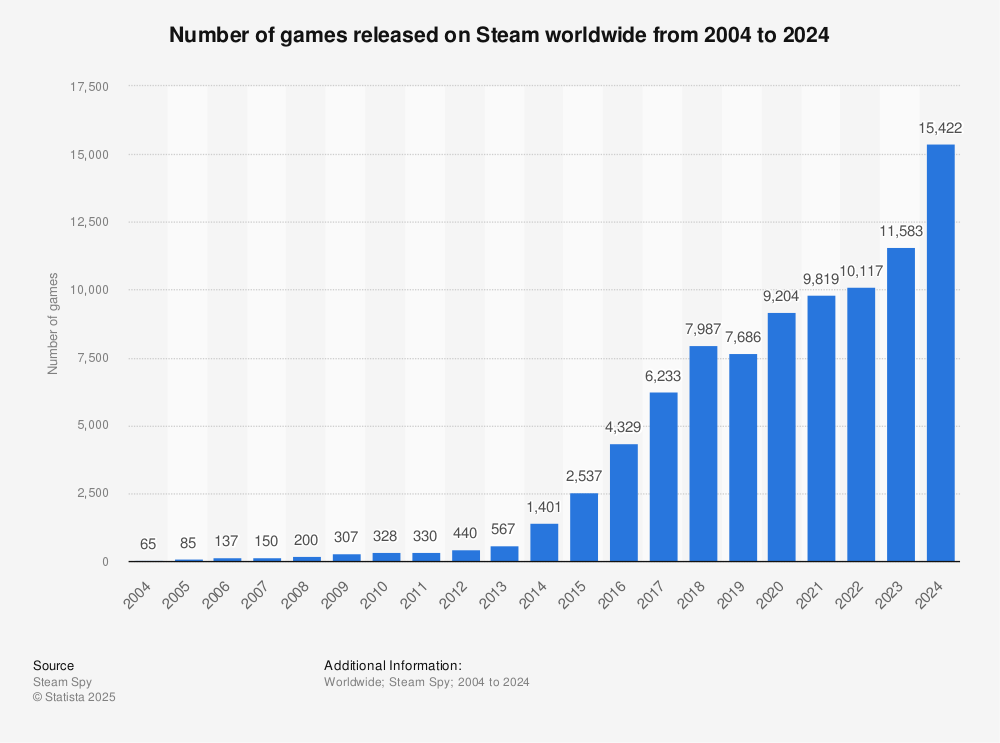

The market has changed. This Steam release chart makes it obvious:

2018's numbers aren't available yet but given that the flood gates are now open, you can imagine what that looks like. Like every other industry that has reduced the barrier to entry, the game industry is filling up with titles. This is (mostly) good for gamers but presents new challenges for game developers.

The Pareto Principle

There are certain mathematical models that become relevant once you are dealing with numbers this high. The most obvious being the Pareto principle.

In games, it works basically like this: The square root of the total competition will earn 80% of the income of a given competitive field.

Let's assume that by end of 2018 there are around 30,000 titles on Steam.

Roughly speaking, that means that in 2018 the top 180 or so will make 80% of the revenue and the remaining 29,800 will share in the remainder of the 20%. As others have noted, Steam's revenue has not been increasing at anywhere near that rate.

In 2017, Steam generated around $4.3 billion versus $3.5 billion in 2016. Or put another way: In 2016 there were 10,000 titles on Steam and in 2017 there were around 18,000 titles on Steam.

This works out to the bottom 9,900 titles on Steam in 2016 sharing $700 million. Or $70,000 for the average for 2016.

But for 2017, while revenue went up to $4.3 billion, the number of titles went up to around 18,000. Which, using the Pareto principle means that that while the 17,800 shared 20% of that amount . Or $48,314 for the average of 2017.

For 2018, let's say the revenue increased by the same rate as it did previously. I don't think this will be the case because of the trend of a few major titles of last year coming out on their own custom platforms. Indeed, if you look at the Steam top sellers for 2018, only three of them were released in 2018.

So for the sake of argument, let's say that total revenue increased to $5 billion last year. That's an impressive increase in total revenue right?

However, while the top 180 or so games will make 80% of that revenue, the bottom 28,800 or so will share in on the remaining $1 billion. Or $34,722 for the average of 2018.

The Pareto principle is a pretty universal axiom used in many industries. It is, what it is. It is a trend that has already occurred in the music and video industries. As the technology and logistics to produce content allow more competition, not only do prices come down but the per product revenue comes down as well regardless of the price. That means developers can't solve this problem by lowering their price. The top 100 or so will always generate around half the total revenue with the top 200 generate around 80% and the rest just will get largely lost in the shuffle.

Discoverability is not the main problem

No matter how perfect Amazon, Steam, GOG, Humble or anyone else makes their discoverability algorithm, it won't change the axiom that that the very top games will generate nearly all the revenue. Discoverability helps to be sure. But it helps at a linear rate of return rather than the exponential rate of the Pareto distribution.

It's easy for a game developer to blame the platform holder. But it's no more Steam's fault that lots of new titles are being submitted than it is Amazon's fault that lots of new digital books are being released. It's not like there were 10,000 games being made per year in 2012 that were being censored. It's just that the rise of inexpensive high end computers for development combined with the amazing tools available to developers has resulted in an explosion of new titles.

So what do you, the developer, do?

There are a number of well tested paths to address this. One of the reasons capitalism works is that it organically generates lots of competitive segments so that the Pareto principle gets split into lots of mini-competitions. For example, Paradox has done well with the "grand strategy game" segment. Being the leader in your niche can translate into a better chance of getting a much, much bigger piece of the pie.

Ultimately, however, it means that we will see a major stratification of game development this year. If you're a major publisher, there is no point in investing in a title that won't be in that top 100.

For Stardock, which has historically worked in the mid-market segment, it means reviewing our own strategy. As a company, we have enough engineers to make a single AAA game but have operated with multiple teams going at once to make mid-market games (Galactic Civilizations, Star Control, Ashes of the Singularity). But as you can imagine, we have seen each game's revenue affected as you would expect.

What is Stardock doing?

Stardock, being an independent developer, has always been able to work on whatever it wants to since it self-funds. This, however, is also a doubled edged sword because it also has meant it errs a bit on the side of caution and thus has not tried to be the "leader" of a given niche but rather the leader of a niche within that niche. I.e. better to spend $3 million to make $15 million in a niche (but also be able to recover if the game fails) than to risk $9 million.

The most obvious example of Stardock's traditional strategy is Galactic Civilizations III. For $3 million invested in generated around $15 million in revenue. But that's nothing compared to Stellaris. Despite being released in 2016 it was the 14th top seller on Steam last year and owns the space strategy genre right now.

When Galactic Civilizations III was being designed in 2012, there were only 1,500 titles on Steam. The risk of making our budget back was very low.

But as we enter 2019, it's a very different world. Spending $3 million knowing you won't be in the top 200 is now a very risky strategy for an independent developer. As other developers have noted, your options are to spend trivial amounts to play the slot machine of indie success or go for the top 200 which means a much bigger risk for an independent studio since one failure could bring down the whole company.

So there are a few things we're thinking of:

- Helping Indies. Like I said, discoverability won't cause the third best fantasy strategy game to suddenly become the top seller, but it can make it can double or triple the game's revenue easily over what it might have done. So this is one area we are looking at is helping promising indies succeed.

- Promising Niches. Stardock is the main user of Oxide's Nitrous engine which allows for emergent game designs. Since it's core-neutral (i.e. the more CPU cores you throw at it, the more it can do) we can make either new types of games or we can do niche games with a fidelity or gameplay that wasn't previously possible. The challenge here is that as we saw with Ashes of the Singularity, a game with a $2 million budget (but has sold almost 800,000 copies) is that many people didn't have 4 CPU cores in 2016. And for Nitrous to really show its advantages, you really need 8 to 16 CPU cores which the market just isn't ready for yet so we still have to design around 4 CPU cores which limits our advantage.

- Embrace our existing niches. With Star Control: Origins, we attempted to go wider. And while the game has done fairly well on PC, its budget was predicated on porting it to consoles which is underway. But rather than going wide with future games, another path is target future games at tighter segments. So for instance, a Star Control II might be a more hard-core RPG. Sins of a Solar Empire has been so successful because it dared to be a multi-hour long RTS. An Ashes of the Singularity II might focus on that kind of depth (i.e. multi-hour games) based on a much richer economic and diplomatic system rather than being a kind of simplified Total Annihilation game.

Regardless of what Stardock does, the game industry as a whole will have to adapt to this model and developers who don't will disappear.